Faculty Friday: Shannon Dudley

It’s an instrument unlike any you’ve ever seen or heard. Tracing its origins to early 20th century Trinidad, the steel pan is constructed by hammering notes into the sunken bottom of an oil drum and played using small, rubber-tipped mallets. But the instrument’s outward simplicity belies complex origins.

“For the people of Trinidad, the steel pan represents irrepressible creativity and a determination to express themselves and assert themselves through music and performance,” says Shannon Dudley, associate professor of ethnomusicology and author of Carnival Music in Trinidad and Music From Behind the Bridge, a history of steelband music in Trinidad.

A tradition brought to the island by French settlers during the 18th century, the island’s annual Carnival served as a “place of license” where Trinidadians could “talk back to power” through music and performance—especially after emancipation of slaves in 1833.

Carnival’s popular expressions of energy and independence unnerved the island’s British colonial administrators, who tried to suppress it. “At one point they effectively banned the use of African drums in Carnival and the end result of that was that people found other kinds of instruments to play,” Dudley says.

“Around 1940 people learned how to tune metal containers to play different pitches and developed this completely new instrument.” And so the steel pan was born.

Over the next half century, awareness and popularity of the unique, chromatically pitched percussion instrument grew, spreading from the streets of Port of Spain, Trinidad to take the musical world by storm, helping catapult calypso music to world consciousness in the process. Dudley first encountered the pan in Ohio when he happened into a steelband classmates at Oberlin had formed together in high school. It revolutionized how he thought about music.

“The steel pan just opened up all these other possibilities for what music could be,” Dudley says. To that point, he played cello and had studied classical music growing up in Berkeley, California.

“Playing in a steelband has always been a much more complete musical experience and remains a touch-point for me for the experience of music as a social activity where people get together to have fun and dance to music and create together.”

A biology major and varsity athlete, Dudley captained Oberlin’s soccer and lacrosse team, but he says it was his involvement in the steelband that made him most proud at the time.

“The only area in which I felt like I was really exploring, creating, pushing the envelope was with the steelband,” he says. Dudley and band mates took seriously the fact the band was a wholly independent outfit without support from faculty. They’d eventually develop a winter-term course to train future band members in an effort to sustain it.

“I dedicated so much time and creative energy to it and we created something that endured beyond our time there,” Dudley says. “What we started there had a staying power and that’s a real great satisfaction to me.”

Then known as “The Oberlin Can Consortium,” the band exists to this day.

‘Pan’ handler

After graduating Oberlin, Dudley embarked on a college-sponsored teaching program in India. For two years, he taught biology, led a school chorus, and helped publish a student newspaper, studying Indian music on his own time. On returning to the US, he once more unpacked his pan.

“When I came back, I just decided let’s spend a little more time with music,” Dudley says. So he tracked down Cliff Alexis, a master builder and tuner of steel pans whose Akron University workshop Dudley had attended as an undergrad.

“I knocked on his door in St. Paul and said, ‘I want to learn how to build steel pans,'” he recalls. Alexis took him on as an apprentice and Dudley helped to sink pan surfaces and learned to shape and groove the notes. After a year, Dudley followed Alexis from Minnesota to Northern Illinois University, the only university in the US with a major in the instrument.

Another year passed and Dudley decided to set aside the pan hammer to pursue a degree in music, applying to UC-Berkeley’s ethnomusicology program. He was accepted on the strength of his practical experience, he says, not having had any prior “formal” musical training.

“At the time, I didn’t really know what ethnomusicology was,” he says.

That was 1986. Three decades later, Dudley says he’s finally figured out what it means to him. “My priority is to give people the experience of making music and to try to help other people have the chance to meet and play music with and learn from great musicians.”

In 1996, he joined the UW, where the visiting artist program remains an anchor of the ethnomusicology program—bringing a performative dimension to a wide-ranging discipline.

“Talking and writing and teaching about music is a way of opening people’s eyes to the roles it plays in our lives and the value it has,” Dudley says. “But I think the chance for our students to work with these artists and to learn from them is what really expands their experience of music.”

For Dudley, it’s imperative that students experience music as a “social art,” especially within an academic setting. To that end, he has worked to build bridges between departments, visiting artists, and the community, “to get people involved making music together as a way of getting to know one another.”

“It’s a way of disrupting the idea that music at the University of Washington is just for experts.”

The UW steelband performs at an Earth Day celebration in Red Square. Founded by Trinidadian steel pan musician and arranger Ray Holman, who served as Visiting Artist in Ethnomusicology at the UW from 1998-2000, the ensemble performs arrangements of calypso, salsa, reggae and other styles. (Photo: Lucas Boland Photography)

‘American Sabor’

One of the major initiatives Dudley is involved in is the Seattle Fandango Project.

“Seattle Fandango Project was an attempt to create a community of people who wanted to get together and make music just to be together and to get to know each other,” Dudley says.

An outgrowth of the four-hundred-year-old tradition of son jarocho from Veracruz, Mexico, the Project hosts weekend workshops where participants gather to dance, sing, and otherwise interact to realize new possibilities and ways of being—both individually and communally.

“You might just as equally value the people who are good cooks and bring food to the event,” Dudley says, alluding to the spirit of convivencia—to convene and coexist—in which the workshops are held. “The idea is that music is something much more broad and social than the way it’s usually conceived in a music department.”

Ten years since it launched, Seattle Fandango Project is going strong. Dudley calls his involvement alongside founding organizers Martha Gonzalez and Quetzal Flores one of his “most inspirational experiences” of the past decade. The Project’s workshops remain a fixture of his Saturdays.

“It’s not one person’s project, but there are a lot of really good people involved in it,” Dudley says. “It’s something that families can do with kids and have family relationships through; I think that’s one of the things that sustains it.”

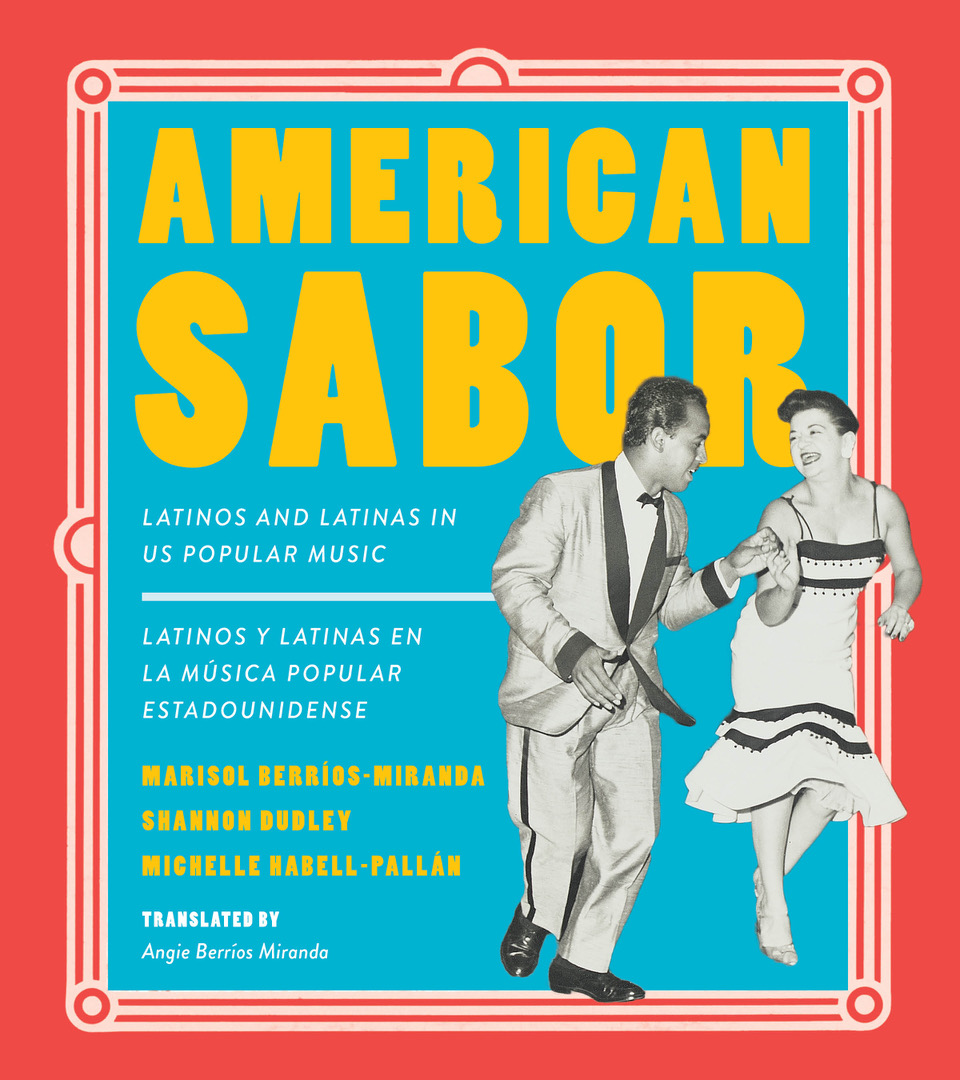

Concurrent with community involvement, Dudley also collaborated with his wife, Marisol Berríos-Miranda, a lecturer in the School of Music Honors Program, and Michelle Habell-Pallan, a UW professor of Gender and Women’s Studies, on the recently published American Sabor: Latinos and Latinas in US Popular Music.

With text in Spanish and English, over one hundred illustrations, and links to online listening, the book is a culmination of a 15-year project that began as a museum exhibit at Seattle’s Experience Music Project and later toured the country, including a three-month run at the International Gallery at the Smithsonian in 2011.

A smaller version of American Sabor prepared by the Smithsonian Traveling Exhibit Services went back on the road. Altogether, the exhibits opened in 18 cities in the US and Puerto Rico.

“Ethnomusicology is the study of culture. You want people to understand not just what music sounds like but who made it and what it means to people,” Dudley told UW News in January when American Sabor debuted. “This book really is about a lot of different local communities and stories that are woven together in a larger picture.”

Challenging the white and black racial framework that structures most narratives of popular music in the United States, the book presents the regional histories of “Latin@” communities—including Chicanos, Tejanos, and Puerto Ricans—in ways that highlight distinctive cultural details as well as shared experiences.

Dudley says the book, like the exhibit, is intended to be accessible to a wide range of people as a work of public scholarship: “We were lucky University of Washington Press was willing to take on a project that was really meant as an academic book, but also as a trade book and possibly as a textbook.”

Amid it all, Dudley still finds time for the steel pan, practicing daily and leading the UW steelband, which plays a major concert each spring as part of the percussion ensemble program as well as performing off- and on-campus throughout the year. Dudley and his wife also play in Dingolay, a three-piece band that plays throughout Seattle including the first Saturday of every month at Pam’s Kitchen in Wallingford.

So what is it about the steel pan that stands out as special for Dudley after playing it for three decades?

“A piano or stringed instrument is very logical—the further you go up the string, the higher the pitch gets—but the steel pan doesn’t have that linearity,” Dudley says. “What blows my mind is that I can play melodies and patterns and improvise them in shapes that I’ve learned in ways where the hand to brain connect is just instant.”

Teaching steel pan has imparted its own lessons along the way, Dudley says.

“One of the things the steel pan teaches me is how amazing the human brain is.”

Shannon Dudley holds a Ph.D from University of California-Berkeley. He teaches courses that include music of Latin America and the Caribbean, American popular music, Music and Community, Comparative Musicianship and Analysis, and graduate seminars in Ethnomusicology.

Seattle Fandango Project’s Saturday workshops are at the Centro de la Raza—learn more here. Learn more about American Sabor here and here. You can catch Shannon playing as part of Dingolay at Pam’s Kitchen in Wallingford the first Saturday of every month.

One Thought on “Faculty Friday: Shannon Dudley”

On October 2, 2018 at 6:48 PM, Barclay said:

Like the imbedded audio interview. Nice article on a fun topic.

Comments are closed.